1 Policy summary

This document provides direction and guidance to all colleagues involved in the assessment, care, treatment, or support of people over 16 years of age who may lack the capacity to make some or all decisions for themselves. It is based on the Mental Capacity Act (2005) (MCA).

It sets out the main provisions of the Mental Capacity Act, identifies the duties placed on health and social care colleagues and provides a procedure to determine the circumstances in which the various processes described within the Mental Capacity Act should be followed.

This policy should be read in conjunction with the Mental Capacity Act (2005) and the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice (2007), as well as the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards Code of Practice (2008), which serves as an addendum to the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

2 Why we need this policy

This document will help the trust to meet its obligations to:

- guide practitioners to ensure patients are supported to make their own decisions where possible

- guide practitioners in providing care to patients who lack the capacity to make specific decisions for themselves

2.1 Aims of the Mental Capacity Act policy

Mental Capacity Act aims to:

- ensure the Mental Capacity Act is used lawfully

- enshrine in statute best practice and common law principles concerning people who lack mental capacity and those who take decisions on their behalf

- make clear who can take decisions, in which situations and how they should go about this

- provide for lasting powers of attorney (LPA) to enable people to plan ahead for a time when they may lose capacity

- the Mental Capacity Act also established a new Court of Protection to make decisions in relation to the property and affairs and healthcare and personal welfare of adults (and children in a few cases) who lack capacity, the court also has the power to make declarations about whether someone has the capacity to make a particular decision

3 Scope

This policy applies to all trust colleagues and should be considered in the care and treatment of patients aged 16 and over. This includes colleagues employed by the trust, social care and health colleagues who are either seconded to the trust or work in partnership with the Trust and volunteers who are working within the trust.

3.1 People covered by the Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act applies to people in England and Wales aged 16 or over who may lack capacity to make their own decisions.

3.2 Younger people aged 16 and 17

Most of the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act apply to young people aged 16 and 17 years old. However, a person needs to be 18 years of age or over to make an advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or a lasting power of attorney (LPA).

Decisions relating to care and treatment of young people aged 16 and 17 who have been assessed as lacking capacity must be made in their best interests in accordance with the principles of the Mental Capacity Act. As part of the best interests process the young person’s family, friends or those with parental responsibility must be consulted where practicable and appropriate.

3.3 Mental Health Act (1983)

If a person is detained under the Mental Health Act (1983), the Mental Capacity Act does not apply to treatment for the person’s mental disorder, which can be given without consent under the Mental Health Act (1983) itself. Therefore, advance decisions and lasting power of attorney’s for health and welfare are not legally binding if they relate to treatment for mental disorder except for electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Attorneys and court appointed deputies cannot consent or refuse treatment for mental disorder given under the Mental Health Act (1983). However, the Mental Capacity Act does apply to treatment for a physical condition or illness for a patient detained under the Mental Health Act (1983).

3.4 Decisions which cannot be made under the Mental Capacity Act

Nothing in the act permits a decision to be made on someone else’s

behalf on any of the following matters:

- consenting to marriage or a civil partnership

- consenting to having sexual relationships

- consenting to a decree of divorce on the basis of two years separation

- consenting to the dissolution of a civil partnership

- consenting to a child being placed for adoption or the making of an adoption order

- discharging parental responsibility for a child in matters not relating to the child’s property

- giving consent under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act (1990)

3.5 Statutory principles

Rotherham, Doncaster, and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust is committed to abide by the five statutory principles which underpin the Mental Capacity Act and will ensure that the key principles are taken into account when applying decisions and actions under the Mental Capacity Act.

Chapter 2 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice expands on the application of the statutory principles.

The five statutory principles are:

- a person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity

- a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help him to do so have been taken without success

- a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision merely because they make an unwise decision

- an act done, or decision made, under this act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done or made in his best interests

- before the act is done, or the decision is made, regard must be had to whether the purpose for which it is needed can be as effectively achieved in a way that is less restrictive of the person’s rights and freedom of action

4 Code of practice

The Mental Capacity Act does not impose a legal duty on anyone to “comply” with the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice, it should be viewed as guidance rather than instruction.

Certain categories of people are legally required to “have regard to” relevant guidance in the code. That means they must be aware of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice when acting or making decisions on behalf of someone who lacks capacity to make a decision for themselves, and they should be able to explain how they have had regard to the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice when acting or making decisions. Where someone has not followed relevant guidance contained in the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice, they will be expected to give good reasons why they have departed from it.

The categories of people that are required to have regard to the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice include anyone who is:

- an attorney under a lasting power of attorney (LPA)

- a deputy appointed by the Court of Protection

- acting as an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA)

- acting in a professional capacity for, or in relation to, a person who lacks capacity

- being paid for acts for or in relation to a person who lacks capacity

The last two categories cover a wide range of people. People acting in a professional capacity may include:

- a variety of healthcare colleagues (doctors, dentists, nurses, therapists, radiologists and paramedics)

- social care colleagues (social workers and care managers)

- others who may occasionally be involved in the care of people who lack capacity to make the decision in question, such as ambulance crew, housing workers or police officers

People who are being paid for acts for or in relation to a person who lacks capacity may include:

- care assistants in a care home

- care workers providing domiciliary care services

- others who have been contracted to provide a service to people who lack capacity to consent to that service

The Mental Capacity Act applies more generally to everyone who looks after, or cares for, someone who lacks capacity to make particular decisions for themselves. This includes family carers or other carers. Although these carers are not legally required to have regard to the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice, the guidance given will help them to understand the Mental Capacity Act and apply it.

4.1 Mental capacity

Mental capacity is the ability to make a specific decision at the time it needs to be made, ranging from a minor decision that affects daily life, to a more significant decision with much wider implications, including a decision that may have legal consequences for themselves or others. Different degrees of capacity are needed for different decisions, and the level of capacity required rises with the complexity of the decision to be made.

The starting point is always to assume that a patient has capacity to make a specific decision, although possibly with help or support. The first statutory principle of the Mental Capacity Act applies equally to people with mental disorder, “a person must be assumed to have capacity unless it is established that they lack capacity”.

It is important to remember that the patient has to “prove” nothing. The burden of proving a lack of capacity to take a specific decision (or decisions) always lies upon the person who considers that it may be necessary to make a decision on their behalf.

Chapter 4 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice expands on the definition of capacity.

4.2 What does it mean to lack capacity to make a decision?

The law gives a very specific definition of what it means to lack capacity for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act. It is a legal test, and not a medical test, and is set down in section 2(1) Mental Capacity Act:

- “a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or the brain”

A person can lack capacity for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act even if the loss is partial or temporary or if capacity fluctuates over time. A person may lack capacity to make one decision but not others.

5 Procedure

5.1 Quick guide

5.1.1 What is the decision?

- Is this a clinical decision or one for the person to make?

- Be clear what the decision is that needs to be made and the options to choose from.

- Decide what information is relevant to the decision, what are the salient details of each option.

5.1.2 Consent

- Assume the person has capacity to make the decision about the proposed action, care or treatment.

- Discuss the options with them including the purpose, nature risks and benefits, of the proposed action, care and or treatment and the consequences of not having it.

- Obtain valid consent from the patient.

- Where there are concerns regarding the person’s ability to consent consider the persons’ capacity to make the specific decision.

5.1.3 Supporting the patient or principle 2

- Before you complete the assessment of capacity, take all reasonable steps to enable a person to make their own decision.

- Provide appropriate support to enable the person to be able to participate in the assessment.

- Consider the persons’ communication needs.

5.1.4 Assessment of capacity section 2 and 3 of the Mental Capacity Act

- Is the person able to make a decision?

- If they cannot, is there an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the person’s mind or brain?

- If so, is the person’s inability to make the decision because of the identified impairment or disturbance?

- Record the evidence of how you came to your conclusion on MCA1 form.

5.1.5 Who decides

- Does the person have a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment?

- Does the person have a relevant registered lasting power of attorney?

- Does the person have a relevant court appointed deputy?

5.1.6 Best interests section 4 Mental Capacity Act

- Identify the relevant options.

- Ensure the person will not regain capacity in time to make the decision themselves.

- Encourage the persons’ participation.

- Take into account the persons wishes feelings beliefs and values.

- Consult with interested parties.

- Avoid discrimination.

- Record the evidence of how you came to your conclusion on MCA2 form.

5.1.7 Protection section 5 Mental Capacity Act

A person is only protected from liability if they:

- have taken reasonable steps to establish whether the individual in question lacks capacity

- the relevant decision-making capacity

- reasonably believe that the person lacks capacity

- believe that the act is in the person’s best interests

- have legal authority to act

5.1.8 Use of restraint section 6 Mental Capacity Act

- Does the person lack capacity to consent to the intervention?

- Is the use of restraint necessary to prevent the person coming to harm?

- Is the restraint a proportionate response to the likelihood and the seriousness of the harm they may suffer?

5.1.9 Deprivation of liberty

- Where the person is subject to:

- continuous supervision and control

- and not free to leave

- and lacks capacity to consent to the placement

- the decision maker will need to consider what legal framework will be used to authorise that deprivation of liberty

- Depending upon the circumstances, this may be the deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS), bringing about admission under the Mental Health Act (1983), or applying to court for an order to authorise the deprivation of liberty.

5.1.10 Settling disputes

- Sometimes people will disagree about a person’s capacity to make a decision what is in a person’s best interests or a decision or action someone is taking on behalf of a person who lacks capacity.

- Where it is not possible to reach agreement on what is in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity, the only place to get an authoritative determination of where those best interests lie is in the Court of Protection.

5.1.11 Court of Protection

The powers of the Court of Protection include:

- making declarations about capacity and best interest’s decisions

- issuing orders about financial and personal welfare matters affecting people who lack capacity, or who are alleged to lack, capacity

- appointing deputies to make decisions for people who lack capacity

- removing deputies or attorneys who act inappropriately

- make decisions about deprivation of liberty

5.1.12 Information sharing

The personal information someone might be able to see about a person who lacks the capacity to give consent will depend on:

- whether the person requesting the information is acting as an agent (a representative recognised by the law, such as an attorney or deputy) for the person who lacks capacity or whether there is a relevant court order in place

- whether disclosure is in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity or whether there is another lawful reason for disclosure

- what type of information has been requested

5.1.13 Research

- If the researchers wish to include a person who they have established lacks the capacity to consent to participate in the research, they must follow the procedures laid down in sections 30 to 34 of the act, including seeking authorisation from an authorised statutory Research Ethics Committee.

5.2 Consent and capacity

5.2.1 What is the decision to be made?

The Supreme Court (in a local authority versus JB) have established that capacity is decision specific. The statement “P lacks capacity” is, in law, meaningless. Colleagues must ask themselves “what is the actual decision in hand”? They must be clear in determining between what is a clinical decision and one which is for the person to make.

The Supreme Court held that in order to determine whether a person lacks capacity in relation to making a particular decision, colleagues should be considering the circumstances of that individual case, for example, the decision may be the same for a number of patients but the relevant information, risks and benefits will be different for each individual.

5.2.2 Relevant information

Once the decision has been established it is important to identify the “information relevant to that decision” which includes information about the reasonably foreseeable consequences of deciding one way or another.

Generally, information relevant to a decision should include:

- the nature of the decision (what)

- the purpose of the decision (why)

- the likely foreseeable consequences of making the decision:

- salient, most important details

- not just consequences for the patient but where relevant consequences for others

- what would a reasonable person in this situation foresee as likely to happen (in the near future)

Relevant information should include the key factors or issues and where the decision is determining between a range of options, the risks, and benefits of each option. It is not necessary for the person to comprehend every detail of the issue but needs to comprehend the salient or most important details.

The Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice states “if a decision could have serious or grave consequences, it is even more important that a person understands the information relevant to that decision”.

It is important not to assess someone’s understanding before they have been given the relevant information about a decision.

The assessor should document a description of the information they consider to be relevant for the person to understand on the MCA 1 questionnaire within the patient record.

The courts have provided guidance on a number of significant decisions as to what constitutes relevant information for the person to understand. This information includes decisions in relation to:

- care

- contact

- contraception

- conducing proceedings

- residence

- discharge from hospital

- hoarding

- medical treatment

- marriage

- use of social media and the internet

- sex

- sharing medical information

The information relevant to the decision may be different, for instance depending on the characteristics of the matter in hand. If there is something different about the “matter” then the relevant information may need to be different.

A pocket guide is available to colleagues for further guidance about relevant information for some of the significant decisions listed above Mental Capacity Act flash cards February 2021 (staff access only). See also more up-to-date guidance from 39 Essex Chambers in the matter of information relevant to the decision.

5.3 Consent

Consent is the voluntary and continuing permission of the person to the intervention or decision in question. It is based on an adequate knowledge and understanding of the purpose, nature, likely effects and risks of that intervention or decision, including the likelihood of success of that intervention and any alternatives to it. Permission given under any unfair or undue pressure is not consent.

All care and treatment decisions should start with colleagues seeking the valid consent of the individual they are working with in accordance with the trusts consent to care and treatment policy.

Where a patient’s capable consent is being relied upon to provide authority for an act of care or treatment or other decision there must be a statement acknowledging this in the patient’s record.

5.3.1 Is the person able to consent to what is being proposed?

If there is reason to believe that a patient is unable to give consent to what is being proposed an assessment of the patient’s mental capacity should be undertaken.

Where the patient is assessed as lacking capacity to make the specific decision lawful authority must be sort from either the Mental Health Act (1983) if the decision is about treatment for a mental disorder and the patient is detained or from the Mental Capacity Act before the proposed action can be carried out or care or treatment can be delivered lawfully.

5.4 Assessment of capacity

5.4.1 Assuming capacity

Principle 1 of the Mental Capacity Act means that when assessing capacity, we must always begin by assuming that a person is capable of making the particular decision unless it can be established otherwise. Before deciding that someone lacks capacity to make a particular decision, it is important to take all practical and appropriate steps to enable them to make the decision themselves.

5.4.2 Supported decision-making

Principle 2 of the Mental Capacity Act says that a person is not to be treated as unable to make a decision unless all practicable steps to help them to do so have been taken without success. This underpins the approach of supported decision-making where colleagues should do all they can to support the person to make their own decision. Colleagues should evidence what practicable steps they have taken to enable the patient to make a decision on the MCA1 form. This may include the information that has been given, who is involved that can help and the way in which this has been done. Colleagues should document the steps they have taken, and any tools or approaches used in this process.

5.4.3 When to carry out an assessment of capacity

Colleagues should think about decision-making capacity every time a person is asked for consent, or needs to make a decision, during care planning.

However, the very act of deciding to carry out a capacity assessment is not, itself, neutral, and the assessment process can, itself, often be (and be seen to be) intrusive. Therefore, colleagues must always have grounds to consider that one is necessary.

Conversely, you must also be prepared to justify a decision not to carry out an assessment where, on face value, there appeared to be a proper reason to consider that the person could not make the relevant decision:

- whilst the presumption of capacity is a foundational principle, you should not hide behind it to avoid responsibility for a vulnerable individual

- if you have proper reason to think that the person may lack capacity to make a relevant decision, especially if the consequence of what they are wanting to do is likely to lead to serious consequences for them, it would be simply inadequate for you simply to record (for instance) “as there is a presumption of capacity, the decision was the person’s choice.” the more serious the issue, the more you should document the risks that have been discussed with the person and the reasons why it is considered that the person is able and willing to take those risks

Capacity should be assessed whenever there is reason to doubt whether the person is able to make a specific decision, particular if they are putting themselves at significant risk.

Concerns may be raised about a person’s ability to make decisions due to the persons behaviour or circumstances, a cognitive impairment which may affect decision-making, or a concern raised by another professional, carer or family member. However, unless you have completed a capacity assessment you should not assume lack of capacity.

Decisions should not be made about a person’s capacity to make a decision based on the person’s age, appearance or unjustified assumptions about capacity based on the person’s condition or behaviour.

Colleagues should also be aware that a person may have decision-making capacity even if they are described as lacking insight into their condition. Capacity and insight are two distinct concepts; if you believe a person’s insight or lack of insight is relevant to their assessment of the persons’ capacity you must clearly record what you mean by insight or lack of insight in this context and how you believe it affects or does not affect the persons capacity.

5.4.4 Doubt about capacity

If there is a belief that a person lacks the capacity to make a specific decision, then it must be demonstrated that on the balance of probabilities that the person lacks the necessary capacity to make the decision at the time it needs to be made. Where clinicians feel a patient is making multiple unwise decisions, this does not mean a patient lacks capacity, but may be an indication that capacity should be assessed.

Where there is doubt about a person’s capacity to make a specific decision, consideration should be given to:

- does the decision need to be made immediately?

- if not, is it possible to delay the decision until the person has capacity to make the decision themselves?

- has everything been done to help and support the person making the decision? (to comply with section 1(3) Mental Capacity Act)

5.4.5 Supporting the person to make the decision

In supporting people to make decisions consideration should be given to the following questions:

- has the person had all the relevant information needed to make the decision in question?

- could the information be explained or presented in a way that is easier for the person to understand?

- are there particular times of the day when the person’s understanding is better or particular locations where they feel more at ease?

- can the decision be put off until the circumstances are right for the person concerned?

- can anyone else help or support the person to make choices or express a view, such as an independent advocate or someone to assist communication?

5.4.6 Who should assess capacity?

The person who assesses an individual’s capacity to make a decision will usually be the person who is directly concerned with the individual at the time the decision needs to be made.

In general terms, the person who is proposing to take a particular action in connection with the care or treatment of an individual will be responsible for assessing the individual’s capacity to consent to that particular action.

This means that different people will be involved in assessing someone’s capacity to make different decisions at different times.

Support may be needed from more experienced colleagues if:

- the decision that needs to be made is complex or has serious consequences

- an assessor concludes that a person lacks capacity, but the person wishes to challenge that decision

- family, carers and, or professionals disagree about a person’s capacity

- there is a conflict of interest between the assessor and the person being assessed

- the person being assessed is expressing different views to different people

- somebody may challenge the person’s capacity to make the decision, either at that time or later

- a vulnerable person may have been abused but lacks the capacity to make decisions that protect them

- a person repeatedly makes decisions that could put them at risk or could result in suffering or damage

As a general rule the more complex the decision the more experienced the assessor should be. There may be times when the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) will discuss the persons’ capacity together however, it is up to the decision maker to assess capacity and conclude they have reasonable belief on the balance of probabilities that the person lacks capacity to make the decision.

5.4.7 Unwise decisions

Everybody has their own values, beliefs, preferences, and attitudes. A person should not be assumed to lack the capacity to make a decision just because other people think their decision is unwise. This applies even if family members, friends, healthcare, or social care colleagues are unhappy with a decision. The act focuses on the ability of a person to make a decision, not on the outcome of the decision itself

There may be a cause for concern if somebody:

- repeatedly makes decisions that appear unwise and puts themselves at significant risk of harm or exploitation

- makes a particular unwise decision that is obviously irrational or out of character.

These circumstances do not necessarily mean that somebody lacks capacity. But there might be a need for further investigation, taking into account the person’s past decisions and choices. For example:

- have they developed a medical condition or disorder that is affecting their capacity to make particular decisions?

- are they easily influenced by undue pressure?

- do they need more information or support to help them understand the consequences of the decision they are facing?

If there is a proper reason to doubt that the person has capacity to make the decision, you should assess their capacity by applying the test in the act.

5.4.8 Assessing capacity

Any assessment of capacity is time and decision specific, for example, an individual may have capacity to choose where they live but not have the capacity to make a decision about their care and treatment. If there is more than one decision to be made, then it will be necessary to undertake more than one capacity assessment.

Capacity assessments should take place face to face with the person, it is not appropriate to make assessments based only on papers or reports.

You should inform the person being assessed of why you are assessing their capacity and what they can do if they do not agree with the outcome.

You must be aware that people may make decisions in different ways. For example, in some culture’s decisions are generally taken individually, whereas other decisions may be made using a more collective approach with others in the family or community. A person’s wish to defer decisions to others could wrongly be taken as indication that they lack capacity, when in fact it is usual for them to make decisions this way.

5.4.9 Applying the test

To assess capacity, first you must carry out the “functional test”. Only if the answer to any of the questions is “no” in the functional test, do we proceed to the second stage of the test which is the “diagnostic test”.

This is in line with the Supreme Court’s decision in a local authority versus JB which said you should consider three questions:

- is the person able to make the specific decision?

- if they cannot, is there an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the person’s mind or brain?

- if so, is the person’s inability to make the specific decision because of the identified impairment or disturbance?

In all cases, though, all three elements of the single test must be satisfied in order for a person to properly be said to lack capacity for purposes of the Mental Capacity Act.

5.4.9.1 Functional test

Mental Capacity Act section 3(1) states that the person is unable to make a decision for himself if he is unable to:

- understand information about the decision to be made (relevant information)

- retain the information in their mind long enough to be able to make the decision

- use or weigh that information as part of the decision-making process

- communicate their decision, this could be talking, using sign language or even simple muscle movements such as blinking an eye

5.4.9.1.1 Understand information relevant to the decision to be made

All practical and appropriate steps must be taken to help a person make a decision for themselves, information must be tailored to an individual’s needs and abilities. It must be in the most appropriate form of communication for the person concerned. Use simple language and pause to check understanding. Where appropriate, use pictures, objects, or illustrations to demonstrate the saliant points.

5.4.9.1.2 Retain that information

It is necessary to retain information for long enough to use it in making the decision. It may be helpful to consider in advance, given the nature of the decision, how long it would reasonably take the person to consider and reach a decision and proceed accordingly. It is not necessary for the person to spontaneously recall information or to retain information long enough for the decision to be implemented, although this may have other practical implications. The fact that the person is only able to retain the information for a short period of time does not prevent him or her from being able to make a decision.

5.4.9.1.3 Use and weigh up the information

As part of the process of making that decision. It is not enough to just understand and retain the information the person needs to be able to consider the consequences of the decision. Keep in mind that individuals may give different weight to different factors. For example, a person may legitimately value independence and familiarity over physical safety or comfort. The Mental Capacity Act does not rely on “lack of insight” and this phrase does not feature in the functional test or Code of Practice.

5.4.9.1.4 Be able to communicate that decision

All attempts should be made to enable a person to communicate their decision, this may include, visual aids, non-verbal gestures etc. A complete inability to communicate is rare, however, in these circumstances the act is clear that a person should be treated as if they are unable to make a decision.

If the person is not able to do any of the 4 elements of the test, you will need to identify what is preventing them from doing so.

If the answer to all four questions is yes, then the person has capacity to make their own decision.

If the answer to any of the above is no, then move to the diagnostic test.

5.4.9.2 Diagnostic test

Is there an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the persons mind or brain?

If it is established that a person is unable to make a particular decision, it is then necessary to show that the person has an impairment of the mind or brain, or some sort of disturbance that affects the way their mind or brain works, and that this has caused them to be unable to make the decision.

If the person does not have an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain, then they cannot lack decision-making capacity for purposes of the act.

Examples of an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain may include the following:

- conditions associated with some forms of mental illness

- dementia

- significant learning disabilities

- the long-term effects of brain damage

- aphasia or dysphasia

- physical or mental conditions that cause confusion, drowsiness, or loss of consciousness

- delirium

- concussion following a head injury

- the symptoms of alcohol or drug use

It is easier to establish that a person has an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain if they have a formal diagnosis of a particular condition. However, a formal diagnosis is not necessary for the purposes of the act. It is also not necessary for the impairment or disturbance to fit into a recognised clinical diagnosis. However, the person claiming that an individual lacks capacity must be able to show a proper basis for considering that they have an impairment or disturbance.

The impairment or disturbance in the functioning of the mind or brain can be temporary or permanent (section 2(2)): if temporary, be careful to explain why it is that the decision cannot wait until the circumstances have changed before the decision is taken.

5.4.9.3 Causal link

Is the person’s inability to make the decision because of the impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain?

In all cases, it is important to be able to answer this third question, sometimes called identifying the “causative nexus”. In other words, are you satisfied that the inability to make a decision is because of the impairment of the mind or brain?

You have to show that you are satisfied why and how there is, a causal link between the disturbance or impairment and the inability to make the decisions in question. The disturbance or impairment in the functioning of the mind or brain must also not merely impair the person’s ability to make the decision but render them unable to make the decision.

There will be situations in which it is not entirely easy to identify whether a person is unable to make what professionals consider to be their own decisions because of:

- an impairment or disturbance in the functioning of their mind or brain (for instance the effect of dementia)

- the influence of a third party (for instance an over-bearing family member)

- a combination of the two

Examples of such cases include:

- the older patient on the hospital ward who looks to their child for affirmation of the “correctness” of the answers that they give to hospital colleagues

- a person with mild learning disability in a relationship with an individual who is clearly cautious about expressing any opinions that may go against what they think may be the wishes of that individual

In such cases, there will sometimes be a difficult judgment call to make whether the involvement of the third party actually represents support for the person in question, or whether it represents the exercise of coercion or undue influence.

Where you have grounds for concern you should seek advice from the Safeguarding team and Mental Capacity Act lead as soon as possible as to what (if any) steps should be taken. In particular, there are some cases in which the right route is not to go to the Court of Protection but rather to make an application to the High Court for declarations and orders under its inherent jurisdiction.

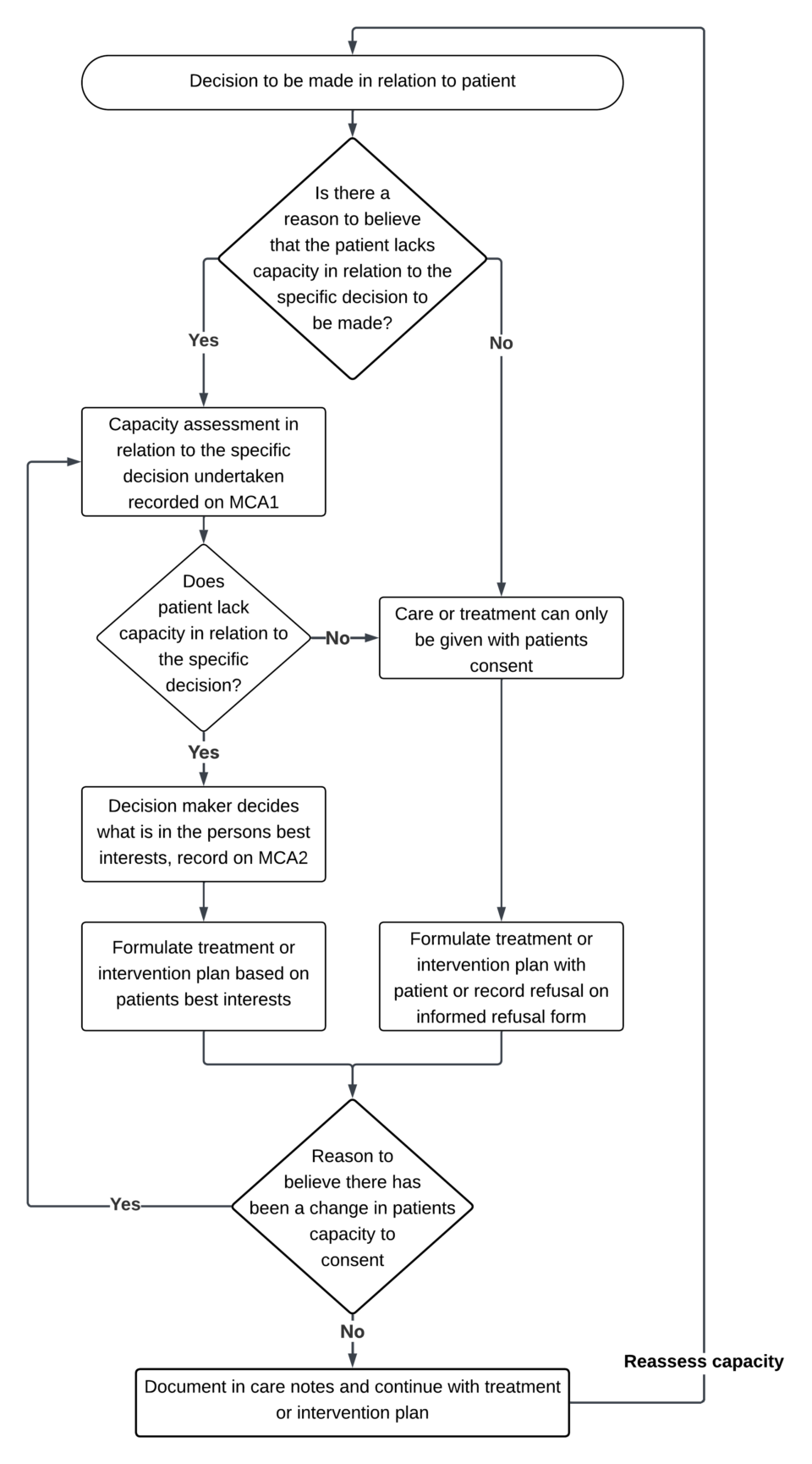

A flow chart in appendix A gives an overview of the process to follow when you have concerns about a person’s capacity.

See also guidance from 39 Essex Chambers on assessment of mental capacity.

5.4.10 Fluctuating capacity

At any given moment, when proposing to provide care and or treatment for a patient or act on their behalf you will have to ask yourself as to the basis upon which you are acting. In the case of a person with fluctuating capacity, there will at any moment be three possibilities:

- the person has the capacity to, and does consent to the intervention in question. At that point, the act could be carried out on the basis of consent

- the person has the capacity to, and does not consent to the intervention in question. At that point, and absent special circumstances (for instance compulsory medical treatment for mental disorder under the Mental Health Act (1983) or an order from the courts), the act could not be carried out because it would give rise to an interference with the persons human rights

- the person does not have the capacity to consent to the intervention in question. At that point, the provisions of section 5 Mental Capacity Act mean that the act could be carried out if you reasonably believed that the person lacks capacity to consent, and you were acting in the person’s best interests

Outside the court setting, it will always be up to the relevant member of colleagues to make the decision whether the person has or lacks capacity at the time that decision needs to be made. In a situation of risk, and given the operational duties imposed by Articles 2, 3 and 8 (European Court of Human Rights), there is likely to be an obligation in a case of fluctuating capacity on the person assessing capacity to explain why in relation to any given decision they determined that the person in question had capacity to refuse a necessary intervention.

If the risks are significant and the person is likely to come to harm if there was no intervention advice should be sought from the Mental Capacity Act lead to help think through:

- whether it really is a case of fluctuating capacity, or a situation where there is a temporary problem with which the person can be supported (as required by section 1(3) Mental Capacity Act).

- if it is a case where the person’s capacity fluctuates, what measures can be taken to support them undertake advance planning to help work out what course of action should be taken at the points when they do not have the capacity to make the decision in question

- if it is genuinely a case of fluctuating capacity, whether it is appropriate to rely upon the informal approach set out above (combined with advance planning)

- whether the Court of Protection should be involved; to decide unusually if it is a “contingency” case where the person has capacity to make the relevant decision but is likely to lose it under very specific circumstances and directions are needed

Some people’s ability to make decisions fluctuates because of the nature of a condition they have. This fluctuation can take place either over a matter of days or weeks (for instance where a person has bipolar disorder) or over the course of the day (for instance a person with dementia whose cognitive abilities are significantly less impaired at the start of the day than they are towards the end).

5.4.10.1 One-off decisions

If it is a one-off decision, it may be possible to put it off until the impact of the person’s condition has diminished. At that point, you should record the person’s decision on the MCA1, and, at least in any case where there may be a challenge later to the decision on the basis that they lacked capacity, record why you consider that the person had capacity to make it.

Depending upon the context, you should also record in an advance care plan what the person would want in the event that they lose capacity in future to make similar decisions or ask them to create an advance statement or advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT). This means that, if the same decision needs to be taken in the future when they lack capacity in their best interests, it can be taken in the knowledge of what they would want. If it is not possible to put the decision off, then you should take the minimum action necessary to hold the position pending the person regaining decision-making capacity.

5.4.10.2 Repeated decisions

Some decisions are not one-off and need to be repeated over a period of time. Examples include the management of a physical health condition which requires a multitude of “micro-decisions” over the course of each day or week. Although capacity is time-specific, in such a case, it will usually be appropriate to take a broad view as to the “material time” during which the person must be able to take the decisions in question.

If the reality is that there are only limited periods during the course of each day or week that the person is able to take their own decisions, then it will usually be appropriate to proceed on the basis that, in fact, they lack capacity to do so. This is particularly so where the consequences for the person are very serious if they are taken to have capacity when, in reality, this is only true for a very small part of the time.

If the approach taken here is adopted, you should keep the person’s decision-making ability under review, and reassess if it appears that the balance has tipped such that they have, rather than lack, capacity to take the relevant decisions more often than not.

For more guidance on fluctuating capacity, in particular looking at it in its wider context, see guidance from 39 Essex Chambers on assessment of mental capacity.

5.4.11 Executive functioning

Another common area of difficulty is where a person gives superficially coherent answers to questions, but it is clear from their actions that they are unable to carry into effect the intentions expressed in those answers. It may also be that there is evidence that they cannot bring to mind relevant information at the point when they might need to implement a decision that they have considered in the abstract. Both of these situations are frequently referred to under the heading of “executive dysfunction”.

Executive function has also been described by in the courts as “the ability to think, act, and solve problems, including the functions of the brain which help us learn new information, remember, and retrieve the information we’ve learned in the past, and use this information to solve problems of everyday life”.

Executive dysfunction can impact on a person’s ability to understand information or to use and weigh information and therefore may be a reason why the person lacks capacity, for example, they are unable to use or weigh information due to executive dysfunction. This may manifest as:

- impulsivity

- lack of problem-solving

- lack of initiation

- difficulty planning

- able to say but not to do

- right answers, not able to put into practice

When assessing capacity for someone who may have difficulties with executive functioning it is important to try to understand their specific impairments for example, do they have difficulty in planning, executing, impulse control, and to triangulate that with observations and the accounts of others.

It can be very difficult in such cases to identify whether the person in fact lacks capacity within the meaning of the Mental Capacity Act, but a key question can be whether they are aware of their own deficits, in other words, whether they are able to use and weigh (or understand) the fact that there is a mismatch between their ability to respond to questions in the abstract and to act when faced by concrete situations.

To date there is a lack of case law on this point however:

- you can legitimately conclude that a person lacks capacity to make a decision if they cannot understand or use or weigh the information, that they cannot implement what they will say that they do in the abstract, or (if relevant) that when needed, they are unable to bring to mind the information needed to implement a decision

- but you can only reach such a finding where there is clearly documented evidence of repeated mismatch. This means, in consequence, it is very unlikely ever to be right to reach a conclusion that the person lacked capacity for this reason on the basis of one assessment alone

- and if you conclude that the person lacks capacity to make the decision, you must explain how the deficits that you have identified and documented, relate to the functional tests in the Mental Capacity Act. You need to be able to explain how the deficit you have identified means (even with all practicable support) that the person cannot understand, retain, use, and weigh relevant information, or communicate their decision

Failing to carry out a sufficiently detailed capacity assessment in such situations can expose the person to substantial risks.

5.4.12 People who will not engage

A problem that can be encountered in practice is where it is difficult to engage the person in the capacity assessment. It is important to distinguish between the situation where the person is unwilling to take part in the assessment, and the one where they are unable to take part.

Justice Hayden emphasised in the matter of QJ: “It is important to emphasise that lack of capacity cannot be established merely by reference to a person’s condition or an aspect of his behaviour which might lead others to make unjustified assumptions about capacity” (section 2(3) Mental Capacity Act).

In this case, an aspect of the person’s behaviour included his reluctance to answer certain questions. It should not be construed from this that he is unable to. However, it is always important to consider what steps could be taken to assist the person to engage in the process; and record what steps were taken and what alternative strategies have been used.

If it is not possible to carry out a capacity assessment, it is important to consider the reasons why assessment is not possible and what steps should follow. Where assessment is not possible and there are reasons to doubt the person’s capacity, the reasons, and any evidence of them should be recorded. In some cases, it may be appropriate to make an application to the Court of Protection to consider the person’s capacity to make the decision in question.

5.4.13 Recording evidence of a Mental Capacity Assessment

5.4.13.1 Day to day decisions

Not all assessments of capacity need to be recorded on MCA1.

In general terms, where there is no significant risk such as decisions concerning matters of day-to-day personal care, support, and normal activities of daily living these will not normally need to be recorded on an MCA1 and can be included in the patients care plan or notes providing there is evidence that the test laid out in the Mental Capacity Act (as above) has been applied.

Examples might include choosing what clothes the person should wear or deciding what the person should eat for lunch or deciding what daily activities to do.

Other low risk decisions the person may need to make which may require consideration of a person’s capacity to consent such as sharing of information, having a photograph taken, consenting to an assessment or referral to other services will not need to be recorded on an MCA1 and where the person has capacity to consent it should be recorded on the appropriate consent template in the patient record.

5.4.13.2 Significant decisions

In order to document and structure the assessment in a clear way which can be audited and reported on colleagues should record the outcome of the assessment of capacity on the MCA1 questionnaire in the patient record. This can be found in the Mental Capacity Act folder on the clinical tree.

The following are some examples of some significant decisions where assessments of capacity must always be recorded on MCA1:

- admission to hospital

- serious medical treatment decisions, including withdrawing or withholding treatment, colleagues should also refer to the trust’s consent to care and treatment policy

- medical treatment for mental disorder which is not being provided under the Mental Health Act

- medical treatment for a physical condition which has serious risks or consequences

- residence

- contact with others

- sexual relationships

- marriage

- contraception

- termination of pregnancy

- use of social media and the internet

- food and hydration

- hoarding

- property and affairs (finances, entering into a contract, tenancy agreement)

- deprivation of liberty which is not authorised under the Mental Health Act

It is good practice to record assessments for other decisions on MCA1, where:

- the person is objecting, if not authorised by the Mental Health Act (1983)

- where there are issues of dispute with family members or other interested parties

- any other complex decisions which have an impact on the patient’s human rights

Colleagues should evidence all parts of the test on the MCA1. Capacity assessments should be criteria-focussed, evidence based, person-centred and non-judgmental.

As with all documentation, the key general points to remember are:

- contemporaneous documentation is infinitely preferable to retrospective recollection

- do not use statements like “the person was unable to understand, retain, use and weigh or communicate” without evidencing how you came to that opinion

- “Yes or no” answers in any record are, in most cases, unlikely to be of assistance unless they are supported by a reason for the answer

- be clear how you have come to your conclusion

- what is reasonable to expect by way of documentation will depend upon the circumstances under which the assessment is conducted

Clear sound evidence that a person lacks capacity gives legal authority for a decision to then be made in the persons best interests.

If the outcome of the capacity assessment is that the patient has capacity to make the decision, the action that is being proposed will be authorised by the patients consent.

Where a patient’s consent is being relied upon to provide authority for a proposed action there must be a statement acknowledging this in the patient record.

5.4.13.3 Evidence for the courts

In some cases, a more detailed report of capacity may be required by the courts. Regulations, rules, or orders made under the Mental Capacity Act or other statutes may require findings to be recorded in a specific way. For example, the Court of Protection will require the completion of an assessment of capacity (COP3) form for applications for deputyship and community deprivation of liberty applications or may ask for an assessment from colleagues in the form of a witness statement under section 49 of the act or in relation to a deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) challenge under section 21A of the act.

In these cases, colleagues should only provide evidence of capacity assessments if required to do so by a court order. The Mental Capacity Act lead can provide guidance in this circumstance.

5.4.13.4 Recording assessment of capacity for patients in the last day of life (hospice services only)

When a patient has been assessed to be in their last days of life and is unable to consent to their care and treatment due to their deteriorating condition, for example, sleeping most of the time, a mental capacity assessment must be completed as per trust policy.

For hospice services patients only, there is no requirement to complete the MCA1 template.

The record of the mental capacity assessment for these patients must be documented on the mental capacity page of the electronic palliative care coordinating systems (EPaCCS) template in the electronic record.

This documentation must comply with the test of mental capacity laid out in the Mental Capacity Act but completed as a paragraph to include:

- decision to be made, medication and treatment for physical health

- evidence of the functional test, inability to understand, retain, use, and weigh the information relevant to the decision to be able to communicate the decision

- evidence of the diagnostic test, impairment of, or disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain

- evidence of the causal link, is the person’s inability to make the specific decision because of the identified impairment or disturbance?

- conclusion that the person lacks capacity to make decisions about their care and treatment

5.5 Best interests

The best interests principle underpins the Mental Capacity Act. It is set out in section 1(5) of the act. “An act done, or decision made, under this act for or on behalf of a person who lacks capacity must be done, or made, in his best interests”.

If a person has been assessed as lacking capacity, then any act done for, or decision made on behalf of the person lacking capacity must be done or made in that person’s best interests. This principle covers all aspects of financial, personal welfare and healthcare decision-making and actions.

Under the Mental Capacity Act, many different people may be required to make decisions or act on behalf of someone who lacks capacity to make a particular decision for themselves. The person making the decision is referred to as the “decision-maker”, and it is the decision-maker’s responsibility to work out what would be in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity.

Careful consideration should be given to whom the decision-maker is:

- where a deputy has been appointed by the Court of Protection to make welfare decisions such as the one in question then the deputy will be the decision maker

- if an attorney has been appointed under a lasting power of attorney to make such decisions, then the attorney will be the decision maker

- in the absence of a deputy or attorney the decision maker will be the person responsible for the act of care or treatment in question

Because every case, and every decision is different, the law cannot set out all the factors that will need to be taken into account in working out someone’s best interests. Section 4 of the Mental Capacity Act sets out common factors that must always be considered when trying to work out someone’s best interests. These factors are summarised in the checklist here.

- Encourage participation. Every effort should be made to encourage and enable the person who lacks capacity to take part in making the decision. Paragraphs 5.21 to 5.24 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

- All relevant circumstances should be considered when working out someone’s best interests. Paragraphs 5.18 to 5.20 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

- Avoid discrimination. Working out what is in someone’s best interests cannot be based simply on someone’s age appearance, condition, or behaviour. Paragraphs 5.16 to 5.17 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

- Regain capacity If there is a chance that a person will regain the capacity to make a particular decision, then it may be possible to put off the decision until later if it is not urgent. Paragraphs 5.29 to 5.36 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

- Life sustaining treatment. Special considerations apply to decisions about life-sustaining treatment. Paragraphs 5.29 to 5.36 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice.

- The person’s past and present wishes and feelings, beliefs and values should be taken into account. Paragraphs 5.37 to 5.48 Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice

- Consult others. If it is practical and appropriate to do so, consult other people for their views about the person best interests.

Chapter 5 of the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice gives more detail on best interests.

For further guidance on best interests see guidance from 39 Essex Chambers on assessment of mental capacity.

5.5.1 Who decides what is in a person’s best interests?

The Mental Capacity Act does not identify any formal decision-makers. The exceptions are where:

- the person has made a valid advance decision to refuse treatment which applies to the treatment in question. In law, the effect is that the person is deciding, at that point, not to consent to the treatment starting or being continued. Their decision cannot be overridden because others do not think it is in their best interests, (unless detained under the Mental Health Act in relation to the treatment of mental disorder). For further guidance see advance statements and advance decisions to refuse treatment policy

- if a lasting power of attorney or enduring power of attorney (EPA) has been made and registered, or a deputy has been appointed under a court order, then the attorney or deputy will be the decision-maker for decisions within the scope of their authority

- the Court of Protection makes the decision on behalf of the person

In most cases, the person who is going to carry out the act will be thought of as “the decision maker”.

In other cases, the person actually carrying out the act will be acting on the direction or under the supervision of another, or subject to a plan drawn up by someone else. In each case, the person will, themselves, have to be satisfied that they are acting in the best interests of the individual before carrying out the act, but are likely to be relying upon the views set down in the plan. In that case, it will be the person who is responsible for the plan who could be thought of as “the decision maker”.

5.5.2 Recording best interests decisions

Where the person has been assessed as lacking capacity to make a specific decision and no one has been appointed on their behalf to make the decision the person who is proposing the care of treatment or action should make a decision in the person best interest.

Evidence of how the decision was made should be recorded on the MCA2 questionnaire in the patient record and shall include details of the options including the risks and benefits of each option, the person wishes and feeling, beliefs and values and the views of others as to what they believe to be in the persons best interests. Where use of restraint is being considered the decision maker must evidence why it is necessary and a proportionate response to the level of harm the person may suffer if the care or treatment was not given.

5.5.2.1 Patients in the last day of life (hospice services only)

When a patient who is in the last days of their life and has been assessed as lacking capacity to consent to their care and treatment while receiving hospice services there is no requirement to complete the MCA1 template.

The best interests decision for these patients must be documented on the mental capacity page of the electronic palliative care coordinating systems (EPaCCS) template in the electronic record.

This documentation must comply with the best interests process laid out in the Mental Capacity Act but completed as a paragraph to include:

- options and provision of care in line with their best interests, taking into account the person wishes, in consultation with the person family

- refer to the standard example in the appendix A and in the trainee starter pack in the hospice

5.6 Acts in connection with care or treatment

Section 5 of the Mental Capacity Act allows carers, healthcare, and social care colleagues to carry out certain tasks without fear of liability. These tasks involve the personal care, healthcare or treatment of people who lack capacity to consent to them. The aim is to give legal backing for acts that need to be carried out in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity to consent.

Section 5(1) provides possible protection for actions carried out in connection with care or treatment. The action may be carried out on behalf of someone who is believed to lack capacity to give permission for the action, so long as it is in that person’s best interests. The Mental Capacity Act does not define “care” or “treatment”. Section 64(1) makes it clear that treatment includes diagnostic or other procedures.

Actions that might be covered by section 5 include:

- in relation to personal care:

- helping with washing, dressing or personal hygiene

- helping with eating and drinking

- helping with communication

- helping with mobility (moving around)

- helping someone take part in education, social or leisure activities

- going into a person’s home to drop off shopping or to see if they are alright

- doing the shopping or buying necessary goods with the person’s money

- arranging household services (for example, arranging repairs or maintenance for gas and electricity supplies)

- providing services that help around the home (such as home care or meals on wheels)

- undertaking actions related to community care services (for example, day care, residential accommodation, or nursing care)

- helping someone to move home (including moving property and clearing the former home)

- in relation to healthcare and treatment:

- carrying out diagnostic examinations and tests (to identify an illness, condition, or other problem)

- providing professional medical, dental, and similar treatment

- giving medication

- taking someone to hospital for assessment or treatment

- providing nursing care (whether in hospital or in the community)

- carrying out any other necessary medical procedures (for example, taking a blood sample) or therapies (for example physiotherapy or chiropody)

- providing care in an emergency

- providing services that help around the home (such as home care or meals on wheels)

- undertaking actions related to community care services (for example, day care, residential accommodation, or nursing care)

- helping someone to move home (including moving property and clearing the former home)

Some acts in connection with care or treatment may cause major life changes with significant consequences for the person concerned. Those requiring particularly careful consideration include a change of residence, perhaps into a care home or nursing home, or major decisions about healthcare and medical treatment.

5.6.1 Protection from liability

Every day, millions of acts are done for people who lack capacity. Such acts range from everyday tasks of caring (for example, helping someone to wash) to life-changing events (for example, serious medical treatment or arranging for someone to go into a care home).

Professionals will be protected from liability under section 5 if they:

- have taken reasonable steps to establish whether the individual in question lacks the relevant decision-making capacity

- reasonably believe that the person lacks capacity

- have considered whether the person is likely to regain capacity to make this decision in the future, can the action wait until then?

- believe that the act is in the person’s best interests

- Have considered whether a less restrictive option is available

5.6.2 Limitations to protection from liability

If colleagues carry out actions in a way which does not comply with section 5, for example by making a decision or performing an act which is not in the person’s best interests, then they may be held liable for any consequences.

Section 5 does not provide a defence in cases of negligence, either in carrying out a particular act or by failing to act where necessary.

Acts may not be protected from liability where there is inappropriate use of restraint.

Acts may not be protected from liability where a person who lacks capacity is deprived of their liberty without authorisation.

5.7 Restraint

Section 6 of the act imposes some important limitations on acts which can be carried out with protection from liability under section 5.

The key areas where acts might not be protected from liability are where there is inappropriate use of restraint or where a person who lacks capacity is deprived of their liberty without authorisation.

5.7.1 Using restraint

The Mental Capacity Act defines restraint as:

- someone is using restraint if they use force, or threaten to use force, to make someone do something that they are resisting,

- or restrict a person’s freedom of movement, whether they are resisting or not

Colleagues will only attract protection from liability when carrying out an action intended to restrain a person who lacks capacity if the following conditions are met:

- the person taking action must reasonably believe that restraint is necessary to prevent harm to the person who lacks capacity

- and the amount or type of restraint used and the amount of time it lasts must be a proportionate response to the likelihood and seriousness of harm

5.8 Legal authority to act

If actions are going to be taken in consequence of the decision which mean interference with the person’s rights under the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the person is going to be restricted or deprived of their liberty, the decision maker will need to consider whether how those in carrying out those actions are acting lawfully.

5.9 Deprivation of liberty

The Mental Capacity Act on its own cannot authorise a deprivation of liberty.

A deprivation of liberty that is not authorised is unlawful.

There is a deprivation of liberty where a person:

- lacks capacity to consent to decide whether they should be accommodated to be given care or treatment

- and is under continuous supervision and control

- and is not free to leave

A deprivation of liberty can be authorised by:

- a deprivation of liberty safeguards (DoLS) authorisation

- the Mental Health Act (1983), where applicable and appropriate

- the Court of Protection.

It is very important that, wherever possible, steps are taken to put in place the relevant authority before the actions are taken. It is also important to note that an attorney or deputy cannot authorise a deprivation of liberty under deprivation of liberty safeguards, and a parent or guardian cannot authorise a deprivation of liberty for a young person who is 16 or 17.

See Mental Capacity Act (2005) Deprivation of Liberty (DoL) policy and Mental Capacity Act Deprivation of Liberty Code of Practice for further guidance.

5.10 Capacity to consent to admission or remaining in hospital

Where a person has capacity and freely consents to the accommodation arrangements made for their care and treatment regime there can be no deprivation of liberty under the Mental Capacity Act.

For the care to amount to a deprivation of liberty, the person must be unable to give their consent to the accommodation arrangements made for their care or treatment.

In order to give valid consent to admission to, or remaining in, hospital after the mental health has ended the person must have the capacity to consent to the actual care and treatment regime that will be in place for them.

Valid consent requires that the person is given sufficient information relevant to the decision and the information they are consenting in this instance will include:

- that they are or will be in hospital to receive care and treatment for a mental disorder

- the core elements of that care and treatment and measures which may be put in place to supervise the patient for example:

- prescription and administration of medication for the treatment of mental disorder

- observation levels

- time away from the ward may be escorted only

- visits may be supervised

- what steps may be taken in respect of searching of the patient and their property

- what would happen if the patient tried to leave hospital

For consent to be valid it must also be freely given, and the person must not be under any duress or inappropriate pressure. Agreement given under duress, or any other pressure is not consent.

5.11 Necessary goods and services

Colleagues may have to spend money on behalf of someone who lacks capacity to purchase necessary goods and services. For example, they may need to pay for a food delivery or for a chiropodist to provide a service at the person’s home.

In some cases, they may have to pay for more costly arrangements such as house repairs or organising a holiday from the person assets. Colleagues are likely to be protected from liability if their actions are properly taken under section 5 and the goods and services are necessary and in the best interests of the person who lacks capacity.

“Necessary” means something that is suitable to the person’s condition in life (their place in society, rather than any mental or physical condition) and their actual requirements when the goods or services are provided. The aim is to make sure that people can enjoy a similar standard of living and way of life to those they had before lacking capacity.

Colleagues should keep bills, receipts and other proof of payment when paying for goods and services. They will need these documents when asking to get money back.

The Mental Capacity Act does not give a colleagues member access to a person’s income or assets. Nor does it allow them to sell the person’s property.

Anyone wanting access to money in a person’s bank or building society will need formal legal authority. They will also need legal authority to sell a person’s property. Such authority could be given:

- in a lasting power of attorney

- by the Court of Protection in the form of a single decision

- by the Court of Protection by appointing a deputy to make financial decisions for the person who lacks capacity

See Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice Paragraphs 6.56 to 6.66 for further information.

5.12 Excluded decisions

The act covers a wide range of decisions made, or actions taken, on behalf of people who may lack capacity to make specific decisions for themselves. There are certain decisions which can never be made on behalf of a person who lacks capacity to make them, this is because they are so personal to the individual or governed by other legislation.

Nothing in the act permits a decision to be made on someone else’s behalf on the following matters:

- consenting to marriage or a civil partnership

- consenting to have sexual relations

- consenting to a decree of divorce on the basis of two years separation

- consenting to the dissolution of a civil partnership

- consenting to a child being placed for adoption or the making of an adoption order

- discharging parental responsibility for a child in matters not relating to the child’s property

- giving consent under the Human fertilisation and Embryology Act (1990)

- voting

Where a person who lacks capacity to consent is currently detained and being treated under part 4 of the Mental Capacity Act, nothing in the Mental Capacity Act authorises anyone to:

- give the person treatment for mental disorder

- consent to the person being given treatment for mental disorder

5.13 Lasting powers of attorney (LPA)

A power of attorney is a legal document that allows one person (the donor) to give another person (the donee or attorney) authority to make decisions on their behalf which are as valid as if made by the person themselves.

There are two types of lasting power of attorney:

- personal welfare, covering healthcare, social care, and consent to medical treatment

- property and affairs, covering finances, money, and property

5.13.1 Personal Welfare lasting powers of attorneys

Lasting powers of attorneys can be used to appoint attorneys to make decisions about personal welfare, which can include healthcare and medical treatment decisions. Personal welfare lasting powers of attorneys might include decisions about:

- where the donor should live and who they should live with

- the donor’s day-to-day care, including diet and dress

- who the donor may have contact with

- consenting to or refusing medical examination and treatment on the donor’s behalf

- arrangements needed for the donor to be given medical, dental, or optical treatment

- assessments for and provision of community care services

- whether the donor should take part in social activities, leisure activities, education, or training

- the donor’s personal correspondence and papers

- rights of access to personal information about the donor

- complaints about the donor’s care or treatment

The standard form for personal welfare lasting powers of attorneys allows attorneys to make decisions about anything that relates to the donor’s personal welfare. But donors can add restrictions or conditions to areas where they would not wish the attorney to have the power to act. For example, a donor might only want an attorney to make decisions about their social care and not their healthcare.

A personal welfare lasting power of attorney can only be used at a time when the donor lacks capacity to make a specific welfare decision.

A personal welfare lasting power of attorney allows attorneys to make decisions to accept or refuse healthcare or treatment unless the donor has stated clearly in the lasting power of attorney that they do not want the attorney to make these decisions.

Even where the lasting power of attorney includes healthcare decisions, attorneys do not have the right to consent to or refuse treatment in situations where:

- the donor has capacity to make the particular healthcare decision (section 11(7)(a)). An attorney has no decision-making power if the donor can make their own treatment decisions

- the donor has made an advance decision to refuse the proposed treatment (section 11(7)(b)). An attorney cannot consent to treatment if the donor has made a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse a specific treatment. But if the donor made a lasting power of attorney after the advance decision and gave the attorney the right to consent to or refuse the treatment, the attorney can choose not to follow the advance decision

- a decision relates to life-sustaining treatment (section 11(7)(c)). An attorney has no power to consent to or refuse life-sustaining treatment, unless the LPA document expressly authorises this

- the donor is detained under the Mental Health Act (section 28). An attorney cannot consent to or refuse treatment for a mental disorder for a patient detained under the Mental Health Act (1983)

5.13.2 Confirming the existence and validity of a lasting powers of attorney

If staff become aware that the patient may have a lasting power of attorney, it is essential that the staff member checks to ensure the lasting power of attorney is valid and applicable to the decision which needs to be made.

For a lasting power of attorney to be valid, it must be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG).

If you are unsure about the existence of a registered lasting power of attorney, you should apply to search the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) registers to see if someone has another person acting on their behalf.

Find out if someone has a lasting power of attorney, deputy or guardian.

If you have any concerns about a deputy who may not be acting in the person best interests, you should report your concern.

Report concern about attorney deputy guardian.

As part of care planning colleagues should also advise patients that they can set up a health and welfare lasting power of attorney if they have capacity to do so, and support them to do so if appropriate, so that a trusted person can represent their interests and make decisions on their behalf if they do not have the capacity to make decisions themselves at any point. Further guidance can be found at lasting power of attorney.

5.14 Court appointed deputies

5.14.1 Appointing a deputy

Sometimes it is not practical or appropriate for the court to make a single declaration or decision. In such cases, if the court thinks that somebody needs to make future or ongoing decisions for someone whose condition makes it likely they will lack capacity to make some further decisions in the future, it can appoint a deputy to act for and make decisions for that person:

- in the majority of cases, the deputy is likely to be a family member or someone who knows the person well

- deputies must be at least 18 years of age

- deputies with responsibility for property and affairs can be either an individual or a trust corporation (often parts of banks or other financial institutions)

- no-one can be appointed as a deputy without their consent